From Bust to Us

Dan Fogelman, creator of the smash family drama This Is Us, discusses how a feature script that had him so stumped he shelved it halfway through became one of the highest rated, most beloved shows on television.

NBC

Dan Fogelman

NBC

Dan Fogelman

We’ve developed what is a very dangerous way of critiquing art…which is, if something makes you feel something, it has to be rejected as populist or mainstream or manipulative or sentimental. That’s a very dangerous precedent.

Dan Fogelman, the creator behind NBC’s tear-jerking juggernaut This Is Us, isn’t “Hollywood nice,” he’s actual “human-being nice.” He’s carved out a career defined by success—scripting features from Cars and Tangled to Crazy, Stupid, Love—but remains humble and smartly sincere, the kind of fella that self-deprecates not in humble brags, but because he genuinely seems to get that there’s a lot of things bigger than him. As a conversation about the genesis of Us unfolds, it becomes readily apparent that his sincere humanity has, to some significant degree, seeped into This Is Us and its writers' room like a magic elixir and helped make the show not just a boon for the Kleenex people, but something that resonates deep and wide. In an era where both the nation and Hollywood are grappling with acts of ugliness and divisiveness, the show’s strains of humanity, unity, and just plain niceness are timely and powerful salve.

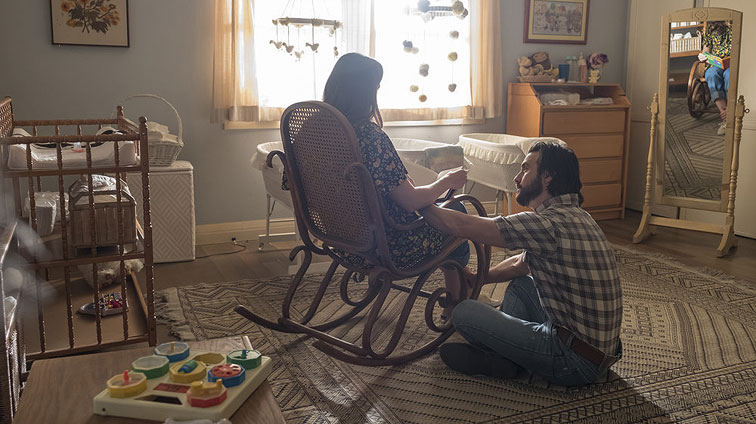

Beyond timeliness, the show is fundamentally sharp storytelling with a powerful time-hopping structure that’s not quite like anything done on television before. While many shows have plumbed the past nostalgically from the present, like The Wonder Years in voiceover, or played with time nimbly to reveal key narrative clues like Lost, Us plays out in parallel times, telling the story of a young family, Jack and Rebecca Pearson (Milo Ventimiglia and Mandy Moore) through the lens of their grown, present day children, a unique set of triplets. This structure, which at times jumps even further back and forth, is not just a fresh gimmick, it is central to an emotive power.

During a conversation with the Writers Guild of America West website, Fogelman discusses his early struggles with This Is Us as a feature script, his habit of jumping into a screenplay with no outline, and how he really, honestly had zero idea that This Is Us would become a show known for making people cry.

This is Us was originally a feature script, and you’ve said it was one of the only times you put something away without finishing it, like 75 pages in. When you shelved it, did you realize it was a TV show or were you just kind of stumped?

No, I was stumped. I sat down to write it as a film, so it wasn’t like my brain at that moment, in the middle of writing it could go, “Oh, this is a TV show.” It was more that it wasn’t gelling as a film, and I was frustrated. So I really put it away out of a place of weakness and giving up.

When and how did it dawn on you that this could be an hour TV drama?

I was starting to think about what a next television project was going to be, and I kept thinking, I want to have a character like that character I wrote, Randall. And I kept thinking that way about other characters, too. Then for the first time it started unlocking that if I went back and reconceived it a little bit, the very thing that was causing me the greatest struggle, which was, what is the plotline of this thing that makes it a film and not just an hour and a half to get to a twist?, suddenly became a strength. A television show answered that question because now it’s not about what the pilot episode is about. It’s about what comes after and how the present affects the past and vice versa. Suddenly I started thinking about the structure of my favorite shows—whether it be the way the West Wing would play with time, or a show like Lost, and it quickly unlocked for me from there.

Audiences are so savvy nowadays. They might not read books anymore, but they know TV and film. How much do you feel the time-hopping aspect is necessary for a show to be compelling now?

Yeah, it’s interesting. I always hesitate to overthink the salesmanship of the show or what it takes to get an audience versus just kind of telling a story and hoping it connects with an audience. Some of our most successful episodes have been the simplest where we’re just following one storyline in linear time and there are barely any flashbacks or flash forwards. So good storytelling is good storytelling. Our show organically and almost accidentally took family drama, or “dramedy” by any other name, and gave it a little bit of urgency and watercooler-ness, because it also created natural how-do-you-get-from-point-a-to-point-b mysteries and questions—things which create an urgency to view the show as a fan, versus the kind of show that might sit on your DVR for two and a half months and you watch whenever you get to it. That really benefited us. Is it necessary to make successful television? Absolutely not. But as a businessman in this business with so much television, your show better either be just really fucking good, or have something that drives the audience to want to get some answers because it’ll be very hard to get attention without that.

And it’s not just a gimmick with this show, it’s a powerfully emotive narrative force, seeing these parallel times, the parents and their grown children…

Yeah, all shows that tread in family and had been successful through the decades have something in them that people can watch and relate to. They relate to the family, there’s something nostalgic about it. What we tapped into—and it’s surprising that no show had done it yet—was the nostalgia of a young family reflected against the present day reality of their grown children. Everybody can relate to that because who amongst us doesn’t look at our life and define it based off our memory of our childhood? Other shows have done [different versions] of it, whether it be The Wonder Years looking back via voiceover, or a show I that I thought was really underrated and didn’t last very long, [Greg] Berlanti’s show Jack & Bobby [on Sci-Fi], which was basically looking back on the childhood of the man who would become president. We just tapped into that. Like, when you’re having a birthday party for your own kids, you think back on the birthday parties your parents used to throw you, and that’s an episode of our show that will make people feel something because they can relate with that.

Because we’re all connected to our childhoods, they’re still alive in a way…

Yeah, that’s the point of our show. When I try and put a point on the show and a positive theme—if there is one overall—it’s that our stories are all remarkably similar. Wherever we grew up, whatever the difficulties with which we struggled, if we were born into money or into poverty, we still had mothers and fathers and complicated relationships with them. We have hopes and dreams and loss and grief. The shared movements of our lives are just very similar. That’s what the show taps into, even though our stories are very different.

And celebrating the power of differences via this universal connection is another engine of the show. Was that a conscious thing at the inception as well, or just something that happened?

Not too conscious. I write a little bit stream of consciousness. I only start writing when I have a general idea or character or characters that excite me, and I just kind of write and at the end of it I have something and hopefully it’s okay. So there’s not a lot of big picture thinking about what it’s actually about as I’m doing it. If you told me three years ago when I was writing this thing that it would become a thing about x, y, or z, or that it would be starting some conversations about race, that wasn’t necessarily in my mind’s eye. I was just writing a story. In making a television series, you start thinking more about that and the responsibilities of that, and trying to bring people who can have a different point of view, so that we’re kind of sharing the collective experience of what we’re all doing here.

So you're not a big outliner?

No. Not that I recommend it, but I don’t outline at all.

You’re just inspired by an idea, and you jump in?

Yes, but it takes me quite a long time to sit down to write that page one, where I feel excited enough that I’m going to kill myself for a bunch of weeks to write something. So I write very fast, and I write very stream of consciousness, but I don’t write very often. With the show, because I write a lot of episodes from scratch, and I do a lot of writing with the other writers, typically my very, very smart writers work out a storyline in the writer’s room. Then, when I’m writing the episode, I’m handed an outline of the episode. Then I take that and go off and write it. We’re just moving at too quick a pace, and the show’s storylines are now so interconnected, that I can’t not have a plan.

You have to pay attention.

Exactly. But when I’m writing an individual movie or a pilot, I just write.

Obviously you are a very successful feature writer. What are the pros and cons in a nutshell between the lone writing style of a feature writer and working with a room on a TV show?

I kind of like everything more about writing a TV show in terms of the actual process of writing, just simply because it’s so collaborative. I love writers in general, so I love hanging with my writers. My responsibilities on the show often bring me to editing or press or to set, so I don’t always get to be full time in the writers’ room, but it’s a treat for me. Right now we’re prepping season three, so I’m getting 10 hours a day in the room with these smart people talking about stories, and it’s my favorite thing. Writing a movie to me—I love writing, but I hate the process of writing. I kind of hole up for a couple of weeks at a time when I’m writing something new, and I’m completely by myself. I separate myself even from my wife and family, and I go off for a week and write. It becomes a real job. I’m trying to write a lot in a short period of time, and get through something and fine tune it as I go. It’s like a mission more. Whereas when I’m with the writers, I’m engaged, and I’m talking, and I’m inspired, and I’m getting inspired…

You're getting energy from other people?

Totally. It breaks up your 12-hour day. Instead of sitting in front of the computer and not speaking out loud for 12 hours, you’re having human connection.

Right. You’re not becoming a troglodyte in a cave.

It’s a crunch. You have to be careful of it. At heart, I’m a writer. I’m directing films now, producing television shows, but at my core, I’m a writer. So you have to be careful about the social aspect of being a television writer because it becomes so captivating and enticing that you stop trusting yourself to sit down in front of that blank page and write words. So that’s always a delicate balance—forcing yourself to not go off and say, “Oh, I have to write this very complicated script, it’s too hard. I can give some of the legwork to my talented writers and not have to write it myself.” You have to be careful not to lose that muscle.

Your process is sounds very organic, obviously, if you’re not outlining and you’re just jumping into it. I’ve talked to some writers who say the characters or the stories just tell them where to go. Is that your vibe when you dive in?

Yeah, typically. Any of the films I’ve done, a film like Crazy, Stupid, Love or any of these somewhat structurally complicated, multi-narrative type films, I typically have been thinking about it loosely for months in the back of my head. I want to do a show about all these different characters who are all linked but in love in a different way and there’s this bachelor and there’s this father and maybe a young woman he’s dating we reveal is the daughter. I kind of had that general shape in my brain. So I’m not sitting down in a vacuum. Then I just start writing. I have a film coming out this year that I wrote that is kind of like the basis of everything I’ve ever written. I let this one take shape over the course of a year, and I kept rewriting and adding to it, and it evolved into a thing. Typically when I get stuck, say I’m on page 50 and I don’t really know how to get to the next point I had in my head, but I know I need a lot of scenes, and I know I need a lot to happen. Rather than sit for a week staring at that Final Draft document and not knowing what to do, I'll open up a Microsoft Word document and start jotting down a loose outline of the next 20 pages of the script. I wouldn’t even call it outlining. And somehow that gets me unblocked, and when I go back to the script I can kind of work off that road map and get myself to where it starts flowing again.

So you used that technique with Life Itself, the pending feature?

Yeah, Life Itself was the most unusual experience I’ve ever had because that was one where I just really started writing. I knew I wanted to tackle some stuff thematically, and I didn’t even know how. I would write a section—because the movie exists in sections and chapters—and step away, and things just started magically falling into place in the script, based off of things that had happened in my life, or suggestions somebody would make to me when I was telling them what I was thinking of. It really revealed itself to me in a really weird, magical way. I’m proud of it, if anything, just because it kind of felt like something weird had happened as I was writing it. It just kind of came out.

Like, you were a conduit for something larger than you?

Yeah. It was strange. It’s a complicated film, and I had an idea for the whole film. I started writing it and I had written like 40 pages, and I gave it to my wife, which I never do early, and she loved it, but she said, “What are you going to do for the rest of it?” And I realized I didn’t really know. That caused me to make a change that led to the whole movie breaking open. Then I was explaining to my producing partner at one point that I wanted to introduce this new character who’s a Puerto Rican kid living in New York, and my friend says, “You always loved Spain so much when you’ve traveled there, why don’t you set it in Spain?” And I said, “Oh, I could make half the movie in Spanish.” It broke the movie open in a different way that pulled it all together. So it really was little kismet things. Bob Dylan serves as the basis of the soundtrack and at the end of writing the film I was in a bookstore with my wife and sitting on a table in the bookstore was this anthology of Bob Dylan criticism. I opened up the book and somebody had written something about a song, and it became the thing that linked the entire film together for me at the end as I was writing. It was one thing after another like that happening that just kind of revealed itself. It had never happened to me like that before.

Did you have a five-season arc for This Is Us at the outset?

Pretty much. It was a four to six season arc depending on length and how I wanted to stretch it out. But I have up to a six-season arc for the show.

How much has the show surprised you, both narratively and in terms of these characters, beyond what you imagined when you were first writing it?

As much as anything in my life. I mean, you don’t sit down and write a little family dramedy and expect it to turn into this. Not just the success and popularity of it, but also the levels it has gone to in terms of where the actors are going and taking the characters. After we cast the actors and made the pilot, I felt we had something special, and I’ve been doing this long enough to know when you do. If I had been a betting man, betting my family’s life on it, I probably would have bet that critics would have responded to it in a positive way and a network audience may have been challenged by it at first, and it could have led to one of those shows that struggles to find an audience. [But] it blew up in such a big way so quickly that once that started happening, everything since then has been surprising.

Suddenly you have Sterling K. Brown and Ron Cephas Jones crushing it in that first season. When we were doing that Memphis episode, you never imagined that it would get to that level of intensity and depth when you were writing their first meeting in the pilot episode. So stuff like that is surprising. And the intensity of Rebecca and Jack, and Jack and his kids and his death, that catches you by surprise. The emotion of the show and the emotional reaction to the show is obviously really surprising. In a million years, I never would have described the show as a thing that’s just going to be making people cry, and that’s the thing that people are talking about. It started happening when I started showing people the pilot, and it was very surprising to me. I thought people were going to gasp at the twists, and I thought people were gonna fall in love with the characters a little bit, and they were going to love Chrissy and Sterling and Milo and all them. When I was seeing men starting to cry, it was catching me off guard. It’s not something we chased, it’s just inherent in the show. There’s something about these actors in these roles and the nostalgia of childhood versus present day that’s just rife with emotion. And that catches me off guard.

You’ve said the show wears its heart on its sleeve. Is there anything you have to do from a writing standpoint to safeguard against getting too sentimental? Or does it just take care of itself?

Well, first you hire the right people. You cast the right actors, and you hire the right writers and directors and editors. So that’s part one. It’s the biggest part of my job and [Ken] Olin’s job and John [Requa] and Glen [Ficarra] and Isaac [Aptaker] and Elizabeth [Berger], all the people that work on the show, to monitor the tone. All you can do is gauge your own taste level, where you think heart and emotion is balanced, and not getting too eye-rolling. Obviously, a cynical critic’s meter is going to be much different than mine, but mine might also hopefully be a little more balanced than somebody else’s. All you can trust is your gut. I know what moves me when I’m watching something. I know what makes me laugh. So hopefully that’s responded to.

We’ve developed what is a very dangerous way of critiquing art…which is, if something makes you feel something, it has to be rejected as populist or mainstream or manipulative or sentimental. That’s a very dangerous precedent because you start saying, if something is going to really move you, it can’t be taken seriously as art. That’s just not the way I live. I am surrounded by people who talk about their parents and their childhoods and their children, and emote and feel, and that is how I view life. What’s going on in our government and politics is pretty bleak and dark right now, but I see people and their stories and they’re beautiful and emotional. I refuse to try and make something sparing and sentiment-less in order to make people say, “Oh, that’s high art.” It’s just not the way I view the world.

Beautifully said. Final question: You’ve talked about how you had to shelve the This Is Us feature script, for aspiring screenwriters, how much do you feel just finishing, whether it’s crap or great, but just finishing, is the biggest battle with writing scripts?

Finishing something is a big, big battle, but I would actually argue that just writing and sitting down to start something new is often the biggest battle. I find with young writers, people double down and triple down and quadruple down on one script. They have to write a script, finish a script, tweak a script—and sometimes that’s not the one that’s going to get produced. That’s the one that led to the next one, that led to the next one, that led to being a better writer. Everybody wants their first script to get read and made and make them millions of dollars as a famous screenwriter. It’s just not the way it works. I wrote screenplays that got me attention, that didn't get made. So I would argue that, rewriting and trying to finish something that people aren’t responding to, or you’re not feeling it’s special—sometimes it's important to finish it so you can get to the next one and become a better writer on the next one and come up with a better idea. Just keep moving. Don’t put all your eggs in one basket. Hopefully you’re a talented enough writer that with the right idea and the right time and the right training, you can write the one that pops.

© 2018 Writers Guild of America West