Murky Waters

Chappaquiddick’s Taylor Allen and Andrew Logan delve deeply into the conflicted character of Edward Kennedy and the murky tale of his involvement in a woman’s drowning death.

Lauren Reynolds

Andrew Logan and Taylor Allen

Lauren Reynolds

Andrew Logan and Taylor Allen

What attracted me most was the character of Ted Kennedy and that his greatest strengths were also his greatest weaknesses. When Taylor and I were talking about ideas and stories to pursue writing, that’s the thing that we look for most: what is the inherent contradiction that the character has?

– Andrew LoganMorally ambiguous characters are the rage these days, as has been on display in epoch-making shows like Breaking Bad, Mad Men, and Game of Thrones. If scripters ever fatigue of morally fraught characters that are made up, there’s no need to panic, modern American history has plenty of real ones in store.

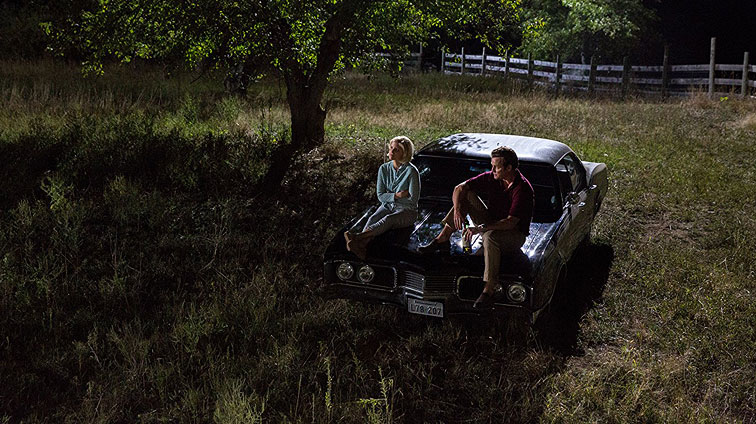

Such is the case with Chappaquiddick, a film directed by John Curran and based on a gruesome event in the early public life of the revered late Senator, Edward “Teddy” Kennedy. The episode in 1969 known as “Chappaquiddick” buffeted an already beleaguered American psyche and changed the course of history. The film was penned by newcomer writing team Taylor Allen and Andrew Logan, whose script centers on the week after the fateful night when Kennedy, then 37 years old, left a party in Martha’s Vineyard and drove his car off a small bridge on Chappaquiddick Island with 28-year-old campaign aide Mary Jo Kopechne in the passenger seat. He managed to escape the sinking car while Kopechne did not. Kennedy left the scene and failed to report it to authorities until the following day, when Kopechne’s body was recovered from the car.

Coming in the wake of the assassinations of two of Kennedy’s brothers, as well as Martin Luther King Jr., the Chappaquiddick incident destroyed Kennedy’s inside shot at the White House in ’72 and added an inglorious chapter to the beatified Kennedy legacy.

Allen, who has worked as an editor on, among others, The Simpsons, and his partner, producer Logan spoke with the Writers Guild of America West website about mining a thousand pages of documents from the original inquest on the matter for their script, and how neither of them had ever even heard of Chappaquiddick until they watched the Bill Maher show in 2007.

What grabbed you about [Ted Kennedy] and ultimately this dark chapter?

Taylor Allen: I have known that I wanted to make and write movies since I was about 10 years old and growing up in Dallas, the Kennedy family looms very large. So I always had a fascination with the history of the Kennedy family and the influence that they had. The person that I was always most interested in was Ted Kennedy because he was the brother that was the hardest to find interesting research about. All the best books were written about JFK at the time and then circa 2000 Bobby came into the forefront with a lot of interesting accounts of what happened in his career. It was so interesting that Ted was the last brother—the last one who survived these three crazy tragedies. The thing that lit up my imagination for him as a character worth exploring on film was because it wasn’t JFK, who was the anointed son. JFK was the sickly younger brother to Joe Jr., and it was only after Joe Jr. died in WWII that suddenly the spotlight went to the next son. Just imagine having such power and such influence in your family, but no one expecting the most from you? It was something I felt I could really relate to, as [I was] the youngest child. I’m very lucky that Andrew had a similar experience growing up in Dallas because again, the city has a lot of Kennedy history.

Andrew Logan: So when we were talking about wanting to collaborate on a screenplay together and we were talking about Ted Kennedy as a character and how interesting he was—we never wanted to set out and write a biopic, cradle-to-grave story because that’s not our taste. So we were discussing what’s the best way to tell the Ted Kennedy story? When we started researching what happened with the Chappaquiddick incident, we felt like we could explore the larger themes of the Ted Kennedy story through this one incident—through the one week when this tragedy happened, culminating in a televised statement that he gives to the country.

Taylor Allen: I have to answer the first part of your question, which is that, honestly—despite the fact that I consider myself a well-educated person, in Texas public schools they’re unable to get past the start of the Vietnam War in U.S. history. So I had never heard that Chappaquiddick happened. It was only when Ted Kennedy was so prominent in the news for endorsing Barack Obama over Hillary Clinton in a game-changing moment that I found out. Andrew and I were in our Beverly Hills slums apartment—we were roommates as soon as we moved out to L.A.—and we were watching Bill Maher on HBO. I don’t know how we afforded it. Bill said something like, Ted Kennedy changing presidential history again, because he would have been president in 1972 had it not been for Chappaquiddick. And he just moved on to New Rules and I was like, “Whoa, whoa, whoa! What is Chappaquiddick?” That’s not a word that rolls off the tongue accidently. I had no idea. Andrew and I hopped on the Google machine, and with the light of the laptop and the TV the only light in the room, we probably sat there for 30 minutes going down a Wikipedia rabbit hole. Even though that’s not the best source of information on the Internet, it links to some better sources, which gets you to some other sources. And that’s how we first got inspired to use Chappaquiddick.

Presumably the endorsement of Obama was a pretty exciting, inspirational thing to hear about. When it’s then comingled with this terrible information that you weren’t aware of, about this women’s death and this tragic event, how did you feel?

Taylor Allen: As a huge Obama supporter I felt that it asked the question, was it worth it to have this man voted into office 30 more years after this incident, in order to get to a moment where his ideas and his ideals made such waves and such great impact for the rest of society? Because at the end of the day, one of the outcomes of Chappaquiddick was always that after Ted Kennedy gave up his presidential ambition in 1980, he became great enough [as a legislator] to be the lion of the Senate and do things that other people encumbered by presidential aspirations might not have been able to do.

Andrew, what appealed to you from a screenwriting standpoint about his complex reality?

Andrew Logan: What attracted me most was the character of Ted Kennedy and that his greatest strengths were also his greatest weaknesses. When Taylor and I were talking about ideas and stories to pursue writing, that’s the thing that we look for most: what is the inherent contradiction that the character has? And we really felt that Ted Kennedy was very sympathetic—as Taylor said earlier, the weight of the Kennedy legacy was unexpectedly thrust on his shoulders, and this accident happened. Then he was trying to see how best to save the Kennedy family legacy, while also asking questions about his own personal goals that conflicts with that. For me that was really rich material for a character arc for a movie.

Ted Kennedy is, at least, a complex, nuanced protagonist. How well does that gray character complexity fit into the style of many scripts today?

Taylor Allen: My joke answer is, we had been watching a lot of Breaking Bad and Mad Man at the time, so that influenced a lot of our thinking. Andrew and I are always interested in taking what the idea of what the protagonist is and having it not be so much about celebrating heroism, but really more about understanding psychology. With Ted Kennedy, he made such clear mistakes. I know that many times he admitted to the mistakes he made that night that led to the tragic death of Mary Joe Kopechne. But those were the choices that he made in the moment, and I don’t think that alcohol or states of shock actually added up to a real explanation. When you started investigating what other people who were there that night said about the state of mind and [Kennedy’s] decision making, it wasn’t that they were forgivable mistakes, but they were understandable mistakes. There’s a clear distinction that I hope I’m making there.

Since you both grew up in the shadow of the Kennedy legacy, and you’re in Ted Kennedy’s general political camp, how did you guard against going easy on him, or being too apologetic in your narrative?

Taylor Allen: We simply wanted to get as close to the truth as possible. That’s why using Andrew Logan’s father lawyerly advice led us to looking for primary sources, and that was the inquest into the death of Mary Joe Kopechne. Everyone was put under oath. Every character in the movie is largely represented in this testimony, which racked up to over 1,000 pages. Even Ted Kennedy himself is under oath there in the Martha’s Vineyard area, speaking about what happened that night. And that’s one of the reasons why the movie itself we hope shows multiple perspectives and multiple tellings of these same events. In doing that, I hope that we reach a greater truth, that what happened was really in between some of these ideas that were publically presented.

From a narrative standpoint, do you feel like the more you dug into the truth, no matter how complicated and difficult, the better the story got?

Taylor Allen: Oh yeah. The quote from me and Andrew through writing the screenplay was that if this screenplay doesn’t work it’s not the fault of the material, it’s our fault as writers. It’s really satisfying when you’re researching and you find gem after gem and you know that as long as you honor the core story, that it will all work because the material is all there. Obviously, that’s one of the reasons it was so attractive to be writing about the Kennedy family—they’re Camelot and American royalty. I would love to write small character dramas that aren’t about famous politicians, but this was a way to make it at the level that I hoped to make it.

This is your first script as a writing team. You guys are buddies, but my understanding is that you wrote with other people before. Why does this partnership work, and why did it take you guys so long to do this?

Andrew Logan: It’s basically 10 years in the making, this partnership and this screenplay. Taylor and I come at filmmaking from different ends of the business. I have been an independent producer for the past seven to 10 years and have produced movies that have been in Sundance and South by Southwest, and Taylor has been an editor, primarily working on The Simpsons. But he also worked on the Edge of Seventeen, and an upcoming movie called Icebox. We were roommates in Los Angeles, and before that we had met in college at film school. Throughout that entire period we had always read each other’s stuff or worked on each other’s short films and critiqued each other’s material, and we always appreciated each other’s honest, unfiltered feedback. We have very similar taste in terms of what stories we’re attracted to. So, we each had separate writing partners for a while, and, I’ll let Taylor say our favorite quote…

Taylor Allen: I’m quoting Matt Weiner quoting Frank Pierson, “It’s after your first divorce that you know what you really want in a second wife.”

You co-write from separate sites via Google docs. What are upsides and downsides of that approach?

Taylor Allen: Andrew and I have always been big fans of John August’s work—not only as screenwriter, but as a philanthropist for the screenwriting path. When he announced the software and the screenwriting language for Highland and Fountain, we were like, that’s so interesting. We had been struggling with other software for collaborating. It was really exciting—because we are kind of techy—to see that we now could write in plain text in any document—in my notes app on my phone, in any computer digital format—and then copy and paste it into our Google Doc, and then export it into Final Draft later. Working over the phone was a necessity for us, so the freedom of not having to have more than your phone with you [was great]. Andrew would often be driving back and forth from Austin to Dallas—his wife is a professional photographer, so she would be driving to Dallas and he would be in the passenger seat on the phone with me, and the phone is doing all the work—it’s connecting us over voice, and he’s in GoogleDocs able to follow along whenever I was typing, and then typing himself whenever he wanted. That was the moment when we were like, “Oh my god, we’ve unlocked a new skill where we can constantly be working with just our phones!” Now the problem with this is Lauren [Andrew’s wife] can only hear half of the dialogue, so it wasn’t very entertaining for her during these three-hour car rides

Would you say the bulk of the writing and drafting was done with the Highland app and just by phone?

Taylor Allen: I would say that we knew from the outline—because we’re religious outliners—that we had something special. So we actually didn't want to write “FADE IN” over the phone. We basically arranged time over Labor Day weekend so I could come to Austin, and we spent that weekend together. And we started page one, FADE IN, and got through about 10 pages that weekend. Then for the rest of the year, we wrote the [rest of the] script almost entirely over the phone. Although I will say Thanksgiving morning and Christmas Eve at the dinner table was not as fun for our families because we were together in Dallas feverously writing Ted Kennedy stories.

You had a massive amount of documents and diagrams to go through. How long was the outlining process and how pumped were you when it was done? Because when you’ve got a good outline, you generally feel pretty good.

Taylor Allen: We got the transcripts for the inquest testimony in May 2014 and on the third time that you’re reading 1,000 pages, it really starts to click in. That really was our bedside reading for about three months. We really started writing in earnest around the Fourth of July and then we outlined for about two months, mostly on weekends because we were trying to put in 8, 10, 12-hour days on it while we were doing that…

Andrew Logan: This was at a time when both Taylor and I had full-time jobs. He was editing and I was producing.

Taylor Allen: But the excitement really did build over those couple of months. Once you have revelations in the research, like finding out that one of the things Ted Kennedy did before he left for Martha’s Vineyard that weekend was give an interview to ABC News, and obviously we knew our climax was going to be a televised statement for the entire nation. That sort of symmetry is the stuff that gets us really excited. So ultimately it was probably a 15-page document—much more sparse then what we do now. The big lesson between Chappaquiddick and other scripts we have worked on since, is that our outlines are the most fun part of the process for us. Unlike other people, we actually find the drafting process to be somewhat mechanical at times. A lot of the best dialogue and the fun moments come out of the outline phase because it’s the moment when he and I are finally together on the phone synthesizing the research that we’ve been doing for months.

That’s really where you’re breaking the story.

Andrew Logan: Oh yeah. And that’s the fun part. You mentioned about having a good outline and feeling really pumped going into the draft, that was the case for this. But what’s funny is that when we finished that first draft it was very, very, very long, at 196 pages.

Oh my.

Andrew Logan: We finished it on a Friday and spent all day Saturday reading it. That Saturday night, when we got on the phone after we both read it, we were like, “This is the worst thing ever.”

Taylor Allen: But it is the thing of writing is rewriting, and editing is a huge part of that. One of the things that's really funny is that we wrote a 196-page script that we hated, then we rewrote three scenes, and we just edited down all the other ones or just cut them out entirely. Once we got down to the 130 range, it was pretty good.

And you guys did obviously pretty well with it. How surprised by the success of the script were you?

Taylor Allen: We never thought anyone would make it. We wrote it to have it read. One of the reasons why the script has a lot of writerly prose stuff going on in it is because it was known to us early on that [for] two kids from Texas that are writing their first screenplay together, the best that we could have ever hoped for is for people to read it and like it. We didn't think that people would want to make it. So when we optioned it and stars started to attach, it was really incredible.

© 2018 Writers Guild of America West